There are very few artworks as famous as The Scream. Edvard Munch’s image of a tortured soul in the midst of a hellish swirling landscape long ago crossed the line from painting to pop cultural icon. This process has divorced it from its art historical context to the degree that it now exists independently of its time, place and even its creator. While The Scream has been reproduced on everything from mouse mats to shower curtains, parodied in a thousand artworks and appeared on countless bedroom walls, its creator has remained an obscure figure, at least outside his native Norway.

This is beginning to change. In 2011 and 2012 Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye, a dazzling exhibition that recast the painter as a modern master, and included his films and photography, went on show at the Pompidou Centre in Paris and Tate Modern in London. This year even more people will be made aware of Munch’s work as exhibitions and events take place in cities across Europe in celebration of the 150th anniversary of his birth.

Anniversary events

Oslo, the city where Munch lived for the greater part of his life, is home to most of the events, including Munch 150, the largest retrospective of the artist’s work to take place anywhere in the world. The retrospective includes around 270 works, and takes place across two major venues: the Munch Museum and the National Gallery.

The show includes the artist’s most famous works – i among them, of course – but it also seeks to transmit the breadth of his enormous output. It’s about “destroying the myth of this artist who did this very dramatic, melancholic work,” says the project co-ordinator Rikke Lundgreen, “showing that he did a lot more”.

The Munch Museum holds nearly 28,000 works by the artist, including paintings, prints, drawings and sculpture, as well as a significant proportion of his personal effects, tools and books. Choosing between them, as well as selecting from the works held by the National Gallery and other public institutions and private collectors in Norway and around the world cannot have been an easy task.

At the heart of the show is a reconstruction of The Frieze of Life, an installation created by Munch at a 1902 exhibition of his work in Berlin. A number of his most important paintings from the 1890s exploring themes including life, death, anxiety and jealousy are presented together against a simple white background, their ornate frames nowhere to be seen.

As well as The Scream, there’s the sexually charged Madonna (1894-5); The Dance of Life (1899), with its depictions of youth, passion and old age; and Death in the Sickroom (1893), Munch’s treatment of the death of his sister in childhood many years previously.

These and the other paintings in The Frieze of Life are masterpieces in their own right – presented together in this way they give a very clear sense of the concerns driving Munch’s artistic practice. Importantly, says Lundgreen, this format also forces viewers to consider the artist’s best-known work as “just another painting in Munch’s production. It makes you look at the painting, not just look at The Scream”.

Hidden works

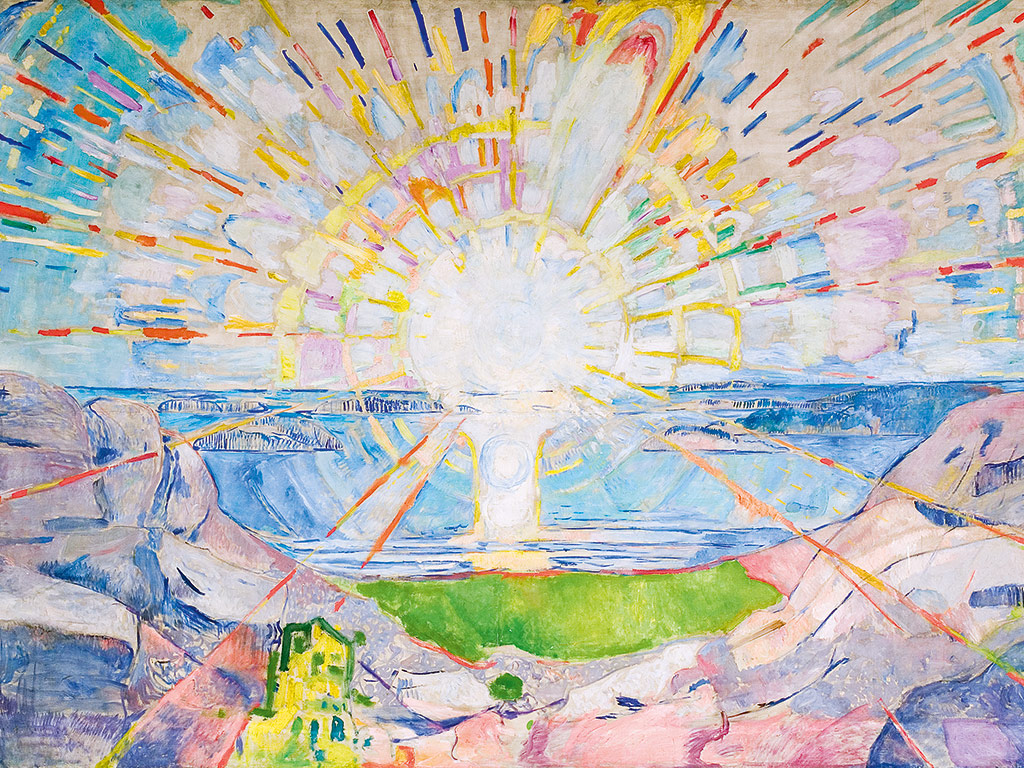

Visitors to Oslo can engage with the artist beyond the walls of the National Gallery and Munch Museum too: the anniversary year offers treats not usually accessible to the public. The most spectacular of these is Munch’s decorations of the ceremonial hall at the University of Oslo, 11 paintings including the three monumental works The Sun, History and Alma Mater that represent different aspects of learning and knowledge. Munch delivered his proposal for the University Aula in 1909 but didn’t complete the commission until 1916 because of controversy surrounding the experimental, expressionistic nature of the works.

More decorative paintings can be found at the Freia Chocolate Factory, the owner of which commissioned Munch to produce works for the building’s new cafeterias in 1919. The oil paintings, which were inspired by the landscape around the painter’s house at Åsgårdstrand, were completed in 1923.

Those interested in the man behind the work can explore the studio at Ekely, the estate on the outskirts of Oslo where Munch lived and worked from 1916 until his death at the age of 80 in 1944. Only the winter studio remains of the buildings inhabited by the artist, but the first house he bought, in Åsgårdstrand on the west coast of the Oslo Fjord, has been preserved as it was during his lifetime. It operates as a museum today.

Lundgreen describes Åsgårdstrand as “a real eye-opener” not just because we can see how Munch lived, but also because it allows visitors to see many of the real life scenes that ended up in his paintings. His bright but brooding 1901 work, The Girls on the Bridge, whose motif was later reproduced by Munch in many different versions in various media, was painted in the coastal town, as was The Dance of Life.

It’s important, says Lundgreen, not to tie Munch’s biography too tightly to his work. It may be tempting to treat an artist’s creations as windows onto his or her subconscious, but this is ultimately reductive: the works, not the personality behind them, should remain the primary focus.

Painting Oslo

That’s not to say, however, that biographical research is not valuable. Or that, for Munch aficionados, learning about the artist and visiting the places that were important to him doesn’t offer an enriching art historical experience.

When it comes to the Norwegian capital, there’s much to be gained from making Munch the focus of one’s explorations. From Oslo’s elegant main boulevard, Karl Johan Strasse, which appears in the anxiety-filled Evening on Karl Johan Strasse (1892), to now-trendy Grünerløkka, the area where the artist grew up, to Ekeberg Hill, the view from which is immortalised in The Scream, Oslo is dotted with places significant in Munch’s life and work. They also happen to be charming locations in their own right, essential stops on any visit to this buzzing city.

On a late summer’s day on Ekeberg Hill, with the waters of the Oslo Fjord shimmering in the sunshine and the city laid out beneath you, it’s hard to get into the mindset that inspired the artist to paint that desperate vision. But perhaps that’s for the best: because though Munch’s most famous work is a masterful portrayal of existential angst, in the painter’s oeuvre as a whole there is light as well as dark, love as well as heartbreak, life as well as death. To fully appreciate his genius, it’s important to pay heed to them all.

The Munch 150 anniversary exhibition runs until October 13. Munch’s studio at Ekely, the University Aula and the Freia cafeteria are open on selected dates until October 13. The artist’s house at Åsgårdstrand is open from May 1 to August 31 each year. Further events related to the Munch 150 celebrations will be taking place for the rest of the year – visit munch150.no