On August 12, 2018, Russia, Azerbaijan, Iran, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan signed the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea, a landmark agreement that had been some 22 years in the making. Strangely, discussions largely centred on whether to treat the world’s largest inland body of water as a sea or a lake.

Prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union (USSR), the decision – which has significant legal, political and business implications – was something of an irrelevance. Until 1991, Iran and the USSR treated the Caspian Sea as a lake with a maritime international border between the two countries. Resources, which at the time were thought to consist mainly of fish, were shared.

With the dispute over how to divide the Caspian Sea now put to bed, further progress can be made

That approach worked just fine until the establishment of Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan as independent nation states complicated matters. They, too, now had territorial claims over the Caspian Sea and its huge oil reserves. Today, both domestic and international corporations are lurking in the background, eager to exploit the commercial opportunities presented by last year’s historic agreement.

As old as the sea

At first glance, the long-running debate over whether the Caspian Sea is a sea or a lake may seem trivial. Legally, however, the distinction is important.

If the body of water is considered a sea, it is subject to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which would allow nations beyond the five surrounding it to make a claim to its resources. If, however, it is deemed to be a lake, it must be split equally between the five littoral states: Russia, Azerbaijan Turkmenistan, Iran and Kazakhstan.

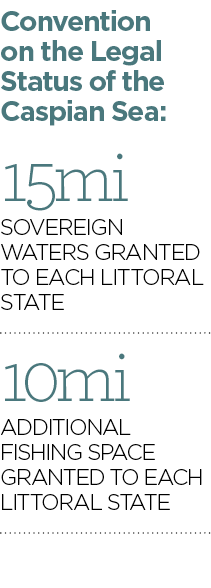

In the end, the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea granted it ‘special legal status’, adjudging it to be neither a sea nor a lake. Each of the five countries has been granted 15 miles of sovereign waters and an additional 10 miles of fishing space. Beyond this, the common waters can be used by any of the signatories, but each state holds a veto regarding the exploitation of energy reserves in these common areas.

Although the Caspian Sea agreement has taken years to negotiate, Stanislav Pritchin, an executive partner at the Expert Centre for Eurasian Development, told Business Destinations that this should be evaluated in light of the complexity of the situation.

“I wouldn’t say that the agreement took too long because you can see examples in many parts of the world where negotiations concerning the delimitations of a sea are still ongoing,” Pritchin said. “For example, the US–Canadian dispute involving the Beaufort Sea remains unresolved and Norwegian–Russian negotiations took several decades. What’s more, these examples only involve bilateral negotiations. In the case of the Caspian Sea, we have five littoral negotiations.”

While the agreement represents significant progress, it has not resolved all of the remaining territorial issues. The delimitation of the seabed and subsoil resources, for example, has deliberately been left undefined, allowing the member states to decide for themselves at a later date. Nevertheless, some are viewing the agreement as a green light to explore commercial opportunities across the sea.

Still waters run deep

Aside from a few substantial sticking points, much of the recently signed agreement has been in place in a de facto sense for some time. As a result, a number of business ventures are already underway across the Caspian Sea. Kazakhstan began commercial production at its Kashagan oil field in 2013, while Azerbaijan’s Shah Deniz gas field has played a key role in the Southern Gas Corridor since 2006.

One of the most important business developments under discussion in the region is the Trans-Caspian Gas Pipeline (TCP), a long-mooted project that would carry Turkmen gas across the Caspian Sea to Azerbaijan and onward to European markets. Not only would this provide much-needed revenue for the Turkmen Government, it would also threaten Russia’s dominance of Europe’s energy mix.

“With regard to the TCP, the convention provides clear rules and a legal framework for underwater projects – not just the pipeline but cable telecoms and other transborder underwater projects,” Pritchin explained. “This means that there are no political or legal restrictions for the TCP – it is only a question of economics.”

Even so, it appears that Russia may have already headed off the threat posed by the TCP. Back in November, Myrat Archayev, the head of Turkmenistan’s state-owned gas company, Türkmengaz, spoke about the possibility of sending the country’s gas supplies towards Eastern Europe via existing Russian pipelines.

While the construction of the TCP is yet to be confirmed, a number of other commercial endeavours are afoot: in December, the Russian ambassador to Azerbaijan, Mikhail Bocharnikov, announced that plans to develop cruise tourism on the Caspian Sea were already underway; Turkmenistan recently invited foreign investors to help exploit the country’s oil potential; Azerbaijan has discussed the development of industrial fish farming; and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani has spoken of accelerating joint projects within the country. As further details of resource sharing are ironed out, more commercial initiatives will surely come to light.

United front

One major hurdle to the development of the Caspian Sea will be more difficult to clear than the others: Iranian sanctions mean that many companies are reluctant to invest in projects in the country, whether they are solely in Iran’s zone of maritime jurisdiction or consist of joint proposals with other states. Unfortunately, western expertise will likely be required for Iran to make the most of its hydrocarbon resources. Alternatively, it could sign deals with Russia or China, but the former already has a number of huge energy deals in the works, and the latter has little experience in deep-water extraction.

Perhaps the most significant benefit of the Convention on the Legal Status of the Caspian Sea is not economic at all: the agreement prevents any country, besides the five littoral states, from having a military presence on the Caspian Sea. For Russia in particular, this is a significant boon, as it secures part of its southern border from possible attack.

“This convention is extremely important for stability in the area because key principles for supporting regional security were agreed,” Pritchin said. “The main one relates to conflict resolution and the other regarding military bases on the Caspian Sea. In addition, no single Caspian state can use its territory for military action against a neighbouring country. In case of a possible conflict, especially in terms of US–Iran tension, there are no threats to Iran from the Caspian Sea dimension.”

Greater regional cooperation also offers hope for the local environment. Pollution caused by sewage from Iran and damage caused by oil and gas extraction pose a threat to the Caspian Sea’s wildlife, especially its sturgeon population. While the agreement may result in further exploitation of the sea’s oil and gas reserves, it also provides a framework for the five member states to work collaboratively on cleaning it up.

Crucially, the Caspian Sea convention should serve as a starting point for further regional integration. With the dispute over how to divide the body of water now put to bed, further progress can be made. Individually, Russia, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan and Iran cannot protect the Caspian Sea from further environmental degradation, nor make the most of its rich resources. Together, they just might.