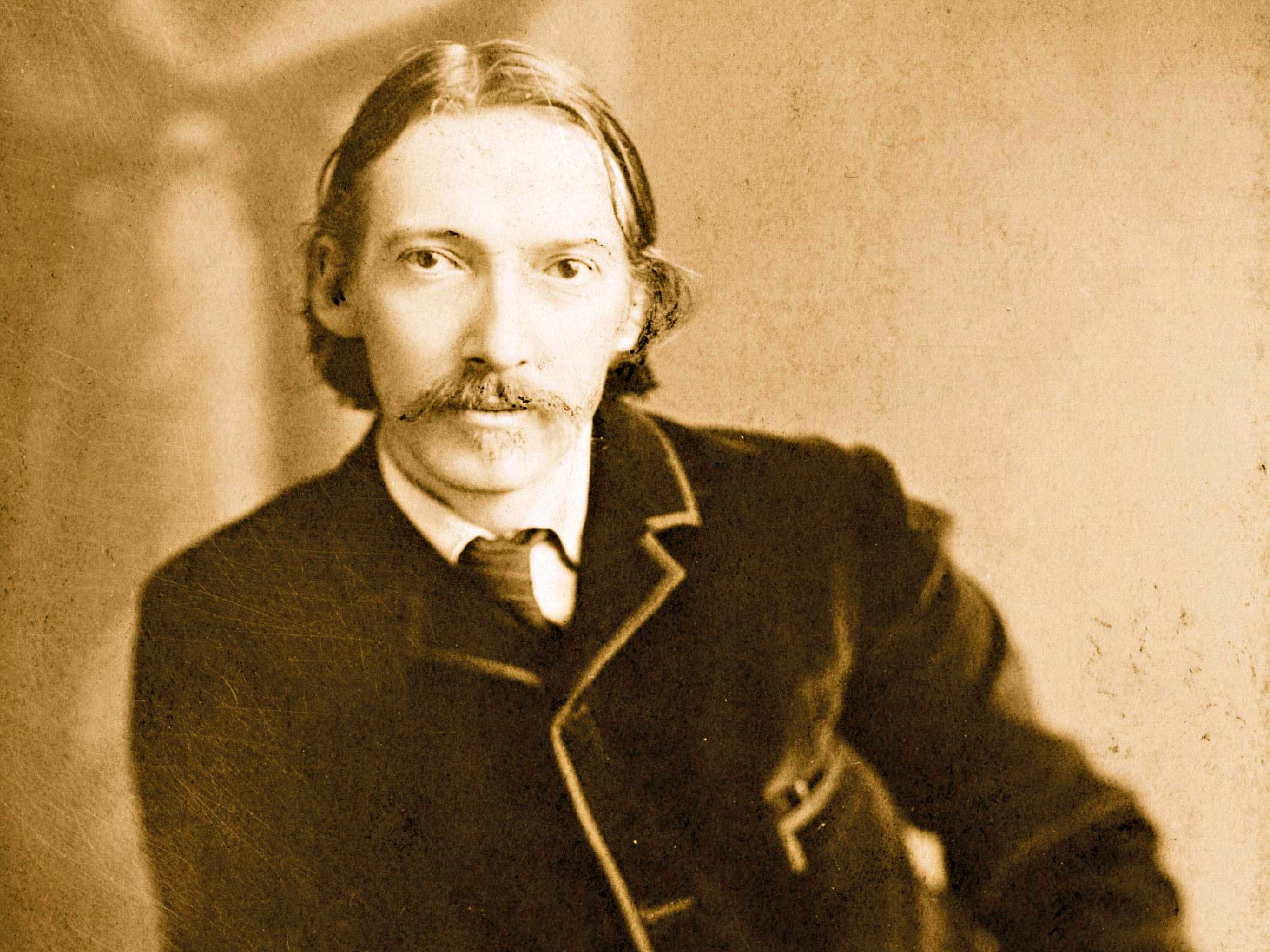

When asked of the impact Robert Louis Stevenson had on the literary world, many would point to his widely renowned works of fiction: Treasure Island and The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. While both beloved texts, fiction was not the source of his initial success. Stevenson’s early travel writing was a driving force for his literary career and has continued to influence the way people write about travel even today.

Of his time, Stevenson was as well travelled as anyone could possibly hope to be. His journeys to the US and his eventual relocation to Samoa made him a travel celebrity, and later informed his work to a tremendous degree. His writing style employed a personal touch that was rare to travel writing at the time, and his focus on individuals rather than cultural stereotypes set his work apart from that of his contemporaries.

Today, modern travel writing is still influenced by his humour, flair and penchant for becoming as much a character in his stories as his subjects. While his tales of pirates and science gone wrong may now overshadow his travel work, any modern traveller owes a debt to the way Stevenson traversed, observed and interpreted the world.

First steps

Stevenson was born to respected parents in Edinburgh on November 13, 1850. His father, Thomas, had built many of the deep-sea lighthouses around Scotland, and his mother, Margaret Isabella Balfour, had hailed from a family of church ministers and lawyers.

Travel played an important role in his life from an earlier age: in 1859, Stevenson’s family went on a three-week holiday to Bridge of Allan, Perth and Dundee in Scotland, and in 1862 they travelled to Bad Homburg vor der Höhe in Germany for the sake of his father’s health. In 1863, the family departed on a three-month tour of Europe, visiting France, Genoa, Naples, Rome, Florence, Venice and Innsbruck. These trips were by no means simple endeavours; the travel industry was in its infancy, and any serious journey represented a large and complex undertaking.

At the age of 17, Stevenson enrolled at Edinburgh University, studying engineering with a view to joining the family business. After abandoning

the course to focus on a law degree instead, Stevenson successfully passed advocate in 1875, but would never practise law professionally.

Today, modern travel writing is still influenced by Stevenson’s humour, flair and penchant for becoming as much a character in his stories as his subjects

It was during his summer vacations from university that Stevenson found his niche in travel writing, with his earliest published works recounting his travels with fellow artists in France. His first volume, An Inland Voyage, was published in 1878, and recalled a canoe trip he made through Belgium and France with his friend Sir Walter Grindlay Simpson in 1876. A year later, Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes was published, describing a hiking trip in France he made with a particularly stubborn donkey. In this piece, Stevenson recounts commissioning a craftsman to make him a custom-designed sleeping sack, one of the earliest examples of a sleeping bag.

Speaking to Business Destinations, Duncan Milne, a PhD scholar at Edinburgh Napier University, said it was these texts that ultimately set Stevenson’s career in motion: “People think he was primarily a writer of fiction, but it wasn’t until he was into his 30s that he was writing novels.”

Stevenson’s early travel texts established him as a somewhat unconventional writer. At the time, many English writers dealing with so-called foreign lands attempted to provide what they considered to be a ‘matter of fact’ representation of a location or its people – often using broad generalisations. Cultures were described in sweeping terms, and regularly compared – rather disparagingly – to the UK.

“It was a very didactic thing and it was very much about imposing your own culture and your own standards on a place you’re walking through,” Milne said. “But Stevenson, making it more personal, was also about being receptive. He’s much more of the style of travel writers from a century later.”

The Amateur Emigrant

Stevenson’s travels would continue throughout his life. After following Fanny Van de Grift Osbourne, the woman he would eventually marry, to the US, Stevenson undertook a remarkable journey across the country in 1879. Upon marrying Van de Grift Osbourne, the pair spent their honeymoon squatting in an abandoned silver mine. These trips would inspire Stevenson’s next volumes: The Amateur Emigrant and The Silverado Squatters.

Milne believes these works exemplify Stevenson’s tendency to focus on people in his travel writing, particularly his meetings with Chinese labourers: “At the time they were the main labour force in America, particularly out west. They were the ones who’d been building the railroad. Stevenson responds to how they were treated.

“He was very much focused on their human individuality, as opposed to a lot of Victorian writers… [who] would tend to sort of homogenise groups, or nationalities or ‘types’ of people in order to generalise.

“And that’s what really strikes me about [Stevenson’s] travel writing, it’s about a series of encounters, encounters with individuals.”

The fiction Stevenson later wrote would build on his experiences of travel, and he was not shy of criticising colonialism

Stevenson continued to travel regularly after he married. Becoming restless in Europe, he set sail across the Pacific Ocean in 1888, jumping from island to island before eventually settling in Samoa. The essays he wrote during his journey were collected in In the South Seas, and retained a focus on individuals. The fiction he later wrote would also build on his experiences of travel, and he was not shy of criticising colonialism.

Milne said Stevenson’s journeys through the Pacific showed a desire to genuinely and honestly interact with different cultures: “He’s not going there as a tourist, he’s not going there as a colonist, he’s going there as somebody who wants to have meaningful encounters with culture, never in a patronising way, as you often have [with] travel writing of that sort, but again in a very humble way.”

Personal perspective

Stevenson often played a primary role in his tales of travel, and he was very willing to poke fun at his own discomfort and awkwardness in strange situations. A classic example is Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes, where he colourfully recounts his inability to get his donkey, Modestine, to move. A local peasant eventually assisted Stevenson, teaching him to bellow the traditional command: “Proot!” Throughout the piece, Stevenson is refreshingly inept and more than a little sheltered.

“He’s very honest about how he responds to things, he doesn’t try to put on a face, he doesn’t try to show how good, and wise and informed a traveller he is,” Milne said. “He admits when he is annoyed, he admits when he is uncomfortable, he admits when he is embarrassed as well.”

However, Milne also revealed that Stevenson’s focus on personal experience was the subject of much criticism at the time. By writing himself so heavily into his work, Stevenson was dismissed as an egoist, and was frequently accused of self-indulgence.

But, when read today, Stevenson’s work has clearly influenced modern travel writing. His style can easily be compared to the latest travel diaries or blogs, and his personal and powerfully honest perspective is easily relatable today. So while the status of his fictional works remains significant, Stevenson’s impact on travel must be considered equally important.