The story goes that, while waiting on a meeting with property developer Irvine Sellar, Renzo Piano haphazardly scribbled an image of a tower on a napkin. With that flash of inspiration was born one of Europe’s tallest buildings, a colossal architectural feat that would later dominate the London cityscape, casting a sail-like shadow upon the river Thames.

The so-called Shard of Glass was christened over a decade later in the summer of 2012, its peak 1,000ft from the ground, the number 32 pasted on its front, and its construction smashing through an estimated £1.5bn. Shortly after came the all-too-familiar flood of criticism, a phenomenon that has followed in the wake of Piano’s greatest creations for nearly half a century.

Early life

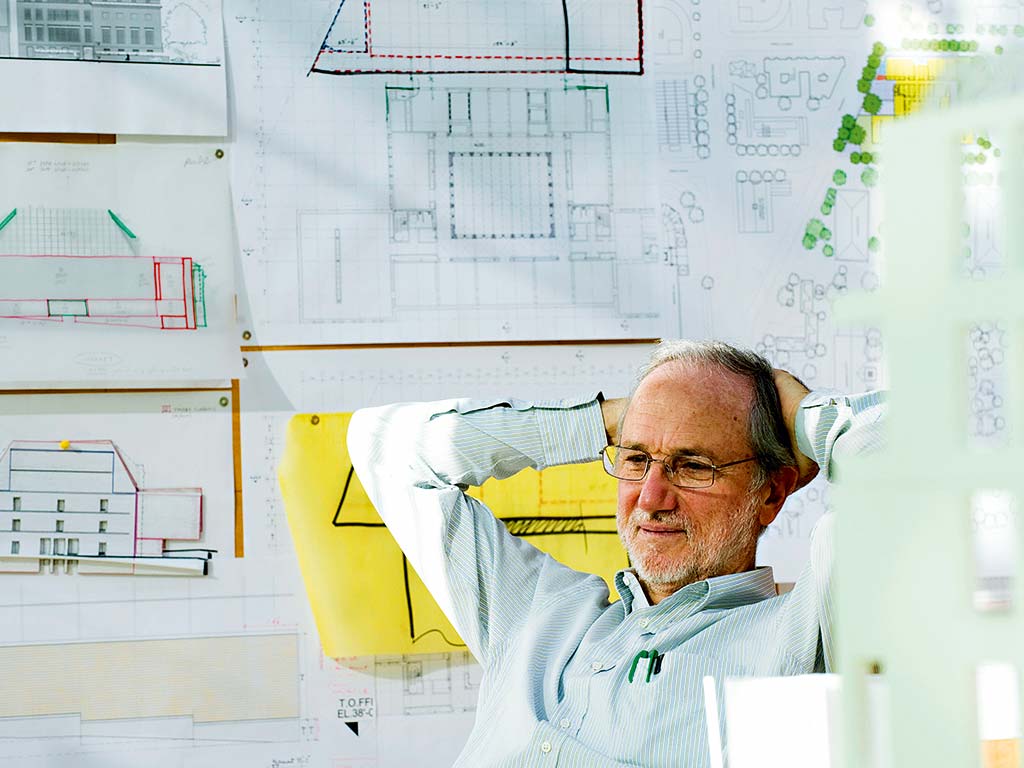

Born in Genoa in 1937, Piano’s beginnings were unremarkable, characterised by an absorption in the world of construction. “My father was a builder and what I loved above all else was to spend time on the site,” recalls Piano. “A construction site is the best place to be when you’re a little boy, it’s where the sand becomes concrete and the brick becomes wall, it’s kind of a magic place where things keep changing.”

A childhood spent amid the bustle of construction sites inspired him, when adulthood came, to enter that world, but from an entirely different angle. Piano showed a fondness for architecture from an early age and as a teenager expressed a desire to enter architecture school. “Why do you want to be just an architect? You can be a builder,” his father would reply.

Nonetheless, Piano attended Milan Polytechnic Architecture School, graduated in 1964 and spent the next year working for his father’s construction company. It was here that he would design under the tutelage of neo-rationalist architect Franco Albini, and begin to hone his craft as an architect.

The next half a decade would be spent travelling and researching until he set up Piano & Rogers with Italian-born British architect Richard Rogers in 1971. It was at this point that his most significant steps into the world of architecture began.

Pompidou Centre

The now iconic partnership of Piano and Rogers soon secured a contract for the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, a space that would later house Europe’s largest collection of modern art and serve as a centre for music and acoustic research. Piano claims it was the “right time to switch from a museum being for a few people, to a place for everyone,” and with this in mind began work on what is perhaps the best-known project of his career.

Piano tested the mores of architectural tradition with the completed article, departing from the cold, sterile brick of conventional museum space and instead opting for a hulking, skeletal frame of steel and glass. The pair designed the building so that elements of construction traditionally concealed were placed in plain sight. In keeping with a theme of functionality present throughout Piano’s career, the building’s components were colour-coded: green for water, blue for air conditioning, yellow for electricity, red for elevators and grey for passageways.

Piano described the museum as “a joyful urban machine… a creature that might have come from a Jules Verne book”. However, the sentiment was not shared by the majority of the viewing public, who reacted to the building with confusion and disdain.

Critics labeled the Pompidou Centre a monstrosity, a stain on Parisian architectural integrity. Rogers told The Telegraph in 2002, “I don’t think we meant to shock. We thought we were solving functional and aesthetic problems of flexibility, growth and change… of course, lots of Parisians simply don’t like that. I was standing outside it and I told an old lady that I was the architect. She hit me with her umbrella.”

Despite the initial response to the so-called Notre Dame des Tuyaux – ‘Our Lady of the Pipes’ – the Pompidou Centre has since been embraced the world over as a seminal work of post-modern architecture. “Fashion goes up and down, but what happens with me is that I go straight,” says Piano. “It’s not difficult to make a new shape, what is difficult is to make a new shape that makes sense.”

Pioneering projects

The architect later founded the Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW) in 1981, which proved an important platform from which Piano’s talent could flourish. The international architectural practice now has offices in Paris, Genoa and New York, employs near 130 people – over 90 of which are architects – and has undertaken upwards of 120 projects in its short history.

One of the better-known of RPBW’s projects is the New York Times Building – named after its principal tenant – which saw the firm capitalising on a neglected corner of Manhattan’s cityscape. The building, completed in 2007, “whose themes of permeability and transparency express the intrinsic link between the newspaper and the city”, is indicative of Piano’s obsession with lightness, present in a great many of his projects. This preference, claims Piano, is rooted in his childhood years spent in Genoa watching sun-soaked ships and noting the likeness they shared with buildings.

Piano’s love of lightness can also be seen in Maison Hermés, a 6,000sq m glass-clad tower set amid Tokyo’s bustling Ginza shopping district, and the Beyeler Foundation Museum, which utilises natural lighting to better illuminate the exhibition space.

However, the most notable of Piano’s projects making use of natural light is the California Academy of Sciences, an innovative project and an international benchmark in sustainable energy production. Its previous incarnation suffered at the hands of natural disaster, with the Loma Prieta earthquake destroying much of its original build in 1989. Piano sought to incorporate this dramatic history into the project’s redevelopment, utilising natural

phenomenon wherever possible in generating the site’s power.

While the undulating curves of the California Academy of Sciences share little in common with the Pompidou Centre from an aesthetic perspective, both demonstrate Piano’s desire to advance and reimagine the practice of architecture. Whether it be the man-made island of Kansai Airport 50km off the coast of Osaka, or the temporary structure of L’Aquila Auditorium, intended to revitalise the city following a disastrous earthquake, Piano’s projects are united by a willingness to push the boundaries of architecture.

Although Piano’s designs have often confounded the public, he is respected the world over as a pioneer of modern architecture, a truly iconic architect whose flair for innovation shows no signs of slowing even as his career nears its half century.