“I now know, by an almost fatalistic conformity with the facts, that my destiny is to travel,” wrote Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara in his book, The Motorcycle Diaries: Notes on a Latin American Journey, published in 1993. His trip, which took him from Argentina to Miami, covering more than 5,000 miles through eight countries, would have a profound effect on his world view and future life.

Before hopping onto his 1939 Norton 500cc motorbike, nicknamed La Poderosa or ‘the Mighty One’, with his close friend Alberto Granado, he was certainly sympathetic to the concerns of the working classes, but he also had other things on his mind. At the start of his journey, Guevara’s thoughts centred on upcoming exams, maintaining his current relationship and how best to keep control of their unwieldy ride.

Although Guevara didn’t set out on his tour in search of social injustice, it is not surprising that he found it

As he made his way across South America, the changes in Guevara were clearly evident. Just as he was amazed by the kindness of those he met, he was also moved by their suffering. During his travels, he came across exploited workers, political repression and widespread poverty. These were the injustices that would set his revolutionary spirit ablaze.

Life on the road

Before setting off on his travels around South America, there was little to suggest that Guevara would go on to become one of the most recognisable figures of the 20th century. He grew up as part of a middle-class Argentine family with left-wing sympathies, but it seemed he would be content to live a fairly standard bourgeois life.

In 1948, Guevara enrolled at the University of Buenos Aires to study medicine, but his desire to see the world soon got in the way. In 1950, he set out to explore Northern Argentina using an old bike modified with an Italian Cucciolo engine. This trip may have taken Guevara some 2,800 miles from home, but it couldn’t completely satisfy his wanderlust.

Three years later, putting his degree on hold, Guevara set off again, this time with his friend and fellow medical student Granado beside him. They planned to spend nine months exploring what life was really like for most people in South America, aiming to stretch their meagre resources by making the most of the local hospitality.

In his diary’s preface, Guevara makes it clear that his journal is not meant to be read as a political manifesto nor as a photographic depiction of life in South America. Rather it is a document of what he sees, thinks and feels. While it certainly touches on some of the issues that would inform his later life as a revolutionary figure, it also concerns many more trivial matters.

“This is not a story of heroic feats, or merely the narrative of a cynic; at least I do not mean it to be,” Guevara wrote. “It is a glimpse of two lives running parallel for a time, with similar hopes and convergent dreams. In nine months of a man’s life he can think a lot of things, from the loftiest meditations on philosophy to the most desperate longing for a bowl of soup – in total accord with the state of his stomach.”

Although Guevara didn’t set out on his tour in search of social injustice, it is not surprising that he found it. Many of the indigenous communities living in South America at that time existed in extreme poverty, shut out from the domestic economy. Life expectancy across Latin America averaged just 44 years. Guevara’s decision to end his trip in the US is also telling, particularly given that his anti-American sentiment becomes more prevalent as his journey progresses. In 1960, just a few years after Guevara finished his trip, the average income in Latin America remained just 12 percent of that in the US.

Finding solidarity

Unsurprisingly, given Guevara’s relatively privileged upbringing, his travels proved particularly enlightening regarding poverty in Latin America. While in Valparaíso, Chile, the young medical student came across an elderly woman struggling with asthma, a condition he also suffered from, as well as a heart disorder. Her living conditions were pitiful and there was little he could do to help her.

“It is at times like this, when a doctor is conscious of his complete powerlessness, that he longs for change: a change to prevent the injustice of a system in which only a month ago this poor woman was still earning her living as a waitress, wheezing and panting but facing life with dignity,” Guevara wrote. “In circumstances like this, individuals in poor families who can’t pay their way become surrounded by an atmosphere of barely disguised acrimony; they stop being father, mother, sister or brother and become a purely negative factor in the struggle for life.”

Guevara’s trip was full of moments like this: brief encounters with strangers whom he would never see again, but nevertheless had a profound impact on him. Whether struck by people’s generosity or appalled by the poverty inflicted upon them, Guevara realised that any help he offered would merely treat the symptoms, not the cause of the disease that plagued Latin America. Looking at the elderly woman, he saw not only individual suffering but also “the profound tragedy circumscribing the life of the proletariat the world over”.

Another part of the journey that had a significant impact on Guevara was the time he spent at the leper colony in Huambo, Peru. There, he found 31 patients relying on inadequate medical treatments to ease their suffering while they awaited death. The two travellers’ later visits to other hospitals and leper colonies were equally formative: despite the fact that neither Guevara nor Granado could offer much in terms of medical assistance, the patients were nonetheless grateful to be treated “as normal human beings

instead of animals”.

Just the beginning

As Guevara made his way across the South American continent, there were many moments of levity – the kind you might expect from a 20-something student enjoying time away from his books and lectures. He played football with locals, was chased away after dancing a bit too closely with a mechanic’s wife, and shared many glasses of wine with people he met along the way. In between these moments, though, were times where the tone became much more earnest.

At the end of The Motorcycle Diaries, after witnessing the suffering of the poor, diseased and disenfranchised, Guevara appeared to have found his calling. Although he would go back to complete his medical studies shortly after returning to Argentina, his life would never be the same again.

“I knew that when the great guiding spirit cleaves humanity into two antagonistic halves, I would be with the people,” Guevara wrote. “I know this, I see it printed in the night sky that I, eclectic dissembler of doctrine and psychoanalyst of dogma, howling like one possessed, will assault the barricades or the trenches, will take my bloodstained weapon and, consumed with fury, slaughter any enemy who falls into my hands.”

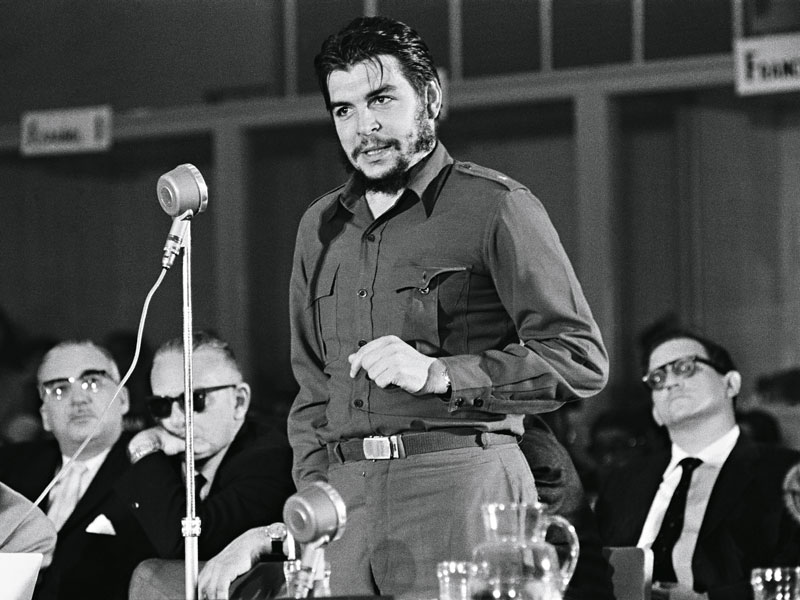

Following a key role in the Cuban Revolution, Che Guevara became a figurehead for left-wing radicals and a symbol of anti-imperialism across the globe. But before he was a revolutionary, a political leader or, to many, an icon, he was an intrepid explorer, keen to see as much of the world as possible.

“Perhaps one day, tired of circling the world, I’ll return to Argentina and settle in the Andean lakes, if not indefinitely then at least for a pause while I shift from one understanding of the world to another,” he wrote. Guevara’s desire to continue travelling did come true – as part of Fidel Castro’s government he visited countries across Europe, Africa and Asia – but he did not get a chance to enjoy a quiet retirement in his home country.

On October 9, 1967, the US-backed Bolivian army executed Guevara, shooting him nine times, before burying him in an unmarked grave. His ideology and beliefs, however – the ones shaped so much by the 5,000-mile journey he took with his friend – continue to inspire people to this day.