Though the Panama Canal will be 100 years old in August, it remains one of the most impressive accomplishments in the field of engineering. It took over 30 years to complete, and 25,000 workers perished during that time, but the result changed the way goods are shipped around the world, opening up a world of opportunity for manufacturing and industries to expand internationally.

To create the 50-mile canal, 42,000 workers shifted a gargantuan amount of earth and water. It lifts enormous vessels 26m above sea level, through a massive artificial lake and thick stretch of impenetrable jungle. But if the canal route seems difficult and dangerous, it’s nothing compared to what seafarers faced before it was built. Ships had to circumnavigate the whole of Latin America – or Africa and the Indian Ocean – to transport a container from one side of the world to the other, but the journey often took them through perilous crossing such as the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn. The latter is a perfect storm of shipping hazards with terrible weather, the extreme southern latitude, and strong currents colluding to bring down ship after ship.

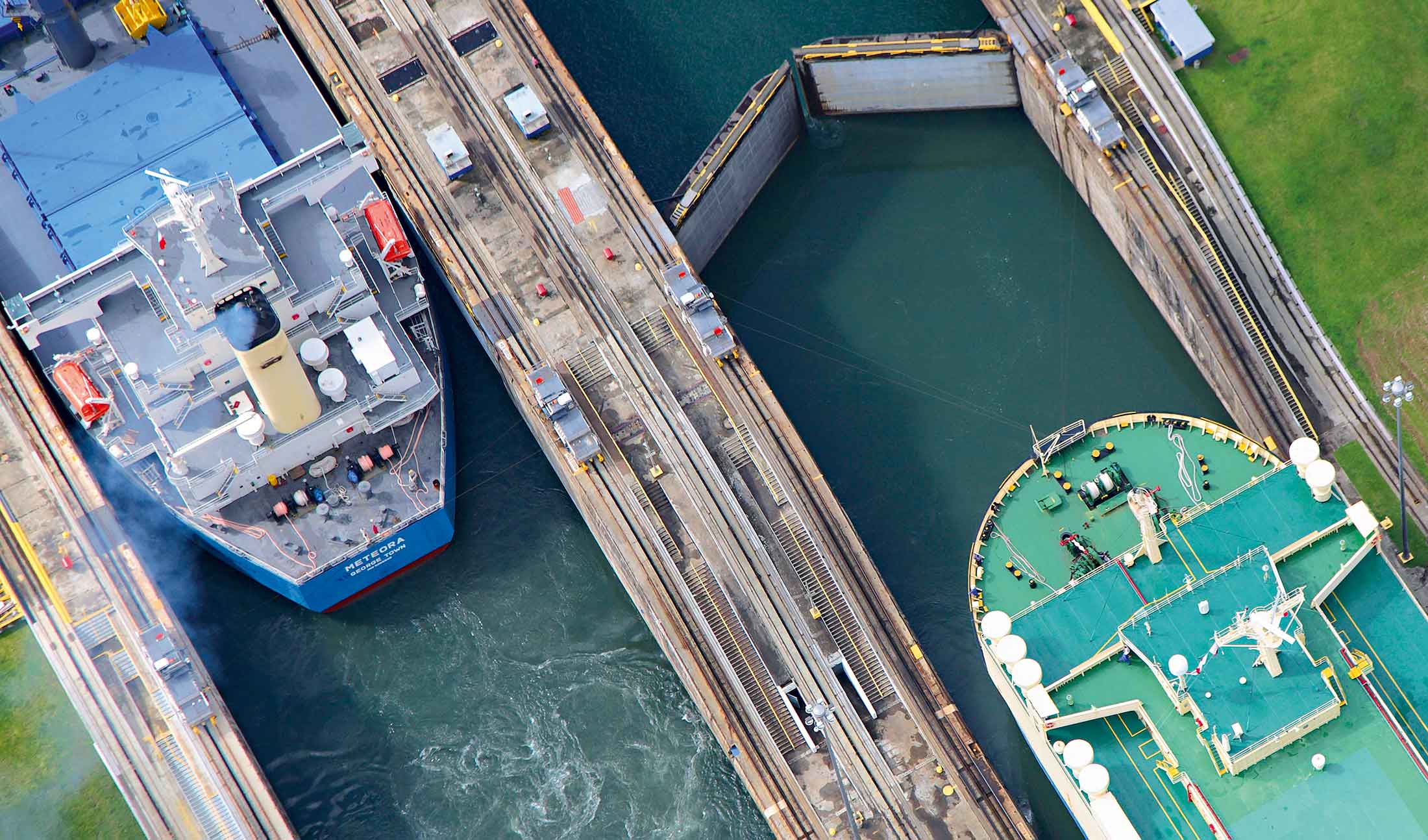

Today, ten percent of all US shipping goes through the canal; it remains a strategic trade route. The canal connects the Port of Colón in the Atlantic Ocean, to Balboa close to Panama City on the Pacific coast. The 50-mile route takes ships through three separate lock gates – one on the Atlantic side before Gatún Lake, and two on the other side, as the ships descend into the Pacific.

For Panama, this project is too big

to fail

The canal is undoubtedly one of the most complex pieces of engineering of modern times. The three locks, Miraflores, Pedro Miguel and Gatún, raise or lower ships three levels, and each of these locks has two gates, enabling two-way transit at every step.

The structure of the canal is vastly complex, even if it is relatively short in length. The 50 miles from the Caribbean to the Gulf of Panama takes a ship from Colón, through the Gatún Locks, where it would be raised 26m above sea level in three steps. It would then travel through the Gatún Lake, perhaps through the Banana Cut, to Gamboa, a port city in the heart of Panama. At the Pedro Miguel Locks, the ship would go down one level, to the height of Miraflores Lake. Across the lake, the Miraflores Locks lower the vessel the final two levels, down to the Pacific Ocean.

The global shipping trade has changed drastically in the last century, but the Panama Canal is carrying more cargo than ever. It has shaped Panama’s economy. There are many challenges ahead though, such as its limited capacity and competition from other shipping routes. Certainly there is a case for the canal to be made more efficient and sustainable, but the investments required run into the tens of billions of dollars. But demand is there, and such an iconic feat of engineering should be kept in use for generations to come.

History

It took over 30 years for the canal to be completed: careers were built and destroyed on it, and thousands of workers lost their lives. But the overall engineering achievement cannot be measured so easily.

Though the Americans take most of the credit for building the canal, it was actually a Frenchman’s vision. Ferdinand de Lesseps, the brain behind the Suez Canal, originally proposed a sea-level canal – that is, a path without locks – and construction began in 1881, with Paris footing most of the bill.

Panama Canal in numbers

1913

September 26, 1913 saw the first voyage of a ship, the SS Ancon

20,000

French men died during construction

15,000

Ships make the crossing each year

$330,000

Highest toll ever paid, by the Disney Magic cruise ship

7,872

Miles between New York and San Francisco, via the canal

However, because of Panama’s location at the heart of the Americas, several kings, emperors and conquistadors had imagined such a waterway, from as early as 1534, when Charles V, King of Spain, ordered a survey of the quickest routes between Peru, his treasure chest colony, and Spain, that would allow him to avoid Portuguese ports along the coast of Brazil.

When gold was discovered in California in the first half of the nineteenth century, plans for a crossing were re-examined, but eventually abandoned in favour of the Panama Railways, opened in 1855. When Lesseps revived the idea some 30 years later, the industrial revolution had increased the need for a route for big trade ships. It also meant that finally there was the technology to build a canal of the proportions required.

But the best-laid plans can go astray, and Lesseps was not even that good to begin with. As the French hurried to break ground because of the strategic trade advantage the canal would offer their ships, research was neglected, and by 1889 it was nowhere near complete, despite costing $287m and the lives of 22,000 workers. Most perished from tropical diseases transmitted by mosquitos from the Panamanian jungle, and the high mortality rate made it hard for work to progress steadily, as there was a near-constant shortfall of experienced workers. Machinery rusted easily in the tropical climes as well, making the endeavour much more costly than originally forecast.

Despite attempts by the French to get the project going again after bankruptcy, it took a trio of American engineers another decade to conclude the canal. John Stevens, appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt, was the man who designed the canal locks when he realised building a pathway 30ft below sea level, through the jungle, would not be feasible, and had already cost his successor John Findley Wallace his job. Colonel George Washington Goethals supervised the final years of the construction. And so, 33 years from the first excavations, the canal was inaugurated in 1914. Despite proclamations that it would take a miracle to complete the project, all it needed was $375m – roughly $8.6bn in today’s money.

The canal has been adapted a few times, first in the 1930s, when it became apparent that there might be a water supply issue, and the Gatún Lake was created by flooding the Chagres River basin. Since then the locks have been modernised, but not much else has been done to it. In 1934 it was estimated that the canal would not be able to carry any more than 80 million tonnes per year; by 2009 canal traffic weighed over 299 million tonnes.

The Panama Canal is resilient and efficient. Over the past three decades, it only closed twice: once during the American invasion of Panama in 1989 and once in 2010 when record-breaking rains flooded the locks. But like any good piece of infrastructure it remains a work in progress, always updating, always bettering, and always facing challenges of the modern age.

Today

Just as important today as it was the day it opened, the Panama Canal carries a greater volume of goods than anyone thought it could cope with, but there are still many challenges ahead.

In 2015 a seven-year project by the Panamanian government to modernise and expand the canal will be completed. Estimated to have cost $5.25bn, shipping lanes were widened and more efficient locks installed to allow a third lane of traffic to open. Though the canal is still fit for purpose, the ever-changing landscape of global manufacturing and shipping means the Panama Canal Authorities and companies who run the concessions must keep reinvesting money to keep it up to date and make sure it can cope with modern vessels and shipping volumes.

Over the past two decades, emerging economies in Asia have changed the focus of transcontinental trade. It has meant the amount of goods shipped globally has risen drastically. Before renovations it was not uncommon for bottlenecks to cause delays for ships waiting to make the crossing, who were sometimes held back 20 to 30 hours. This gave rise to a two-tier system in which bigger companies paid handsomely to be pushed ahead of the queue; in 2009 BP Shipping paid an additional $220,000 to avoid lines.

In 2005, five percent of all shipping traffic passed through the canal, including up to 70 percent of all US shipping goods. In 2007, close to 15,000 ships carrying a record-breaking 313 million tonnes of goods travelled through the Panama Canal – soon after, renovations began. By 2025, it has been estimated that demand will have risen to 510 million tonnes, but the size of the vessels will probably have grown too.

As of 2011, it has been estimated that 37 percent of all operational container ships are Post-Panamax – that is, they are bigger than the maximum size allowed to travel on the Panama Canal. After the renovations, the canal can cope with much bigger vessels, which will travel through new third lane locks.

The modernisation process was also necessary to address building environmental concerns, particularly around water conservations. Originally, 60 percent of the water was reutilised in the locks. In the new set-up, a number of basins have been built around the locks that collect the water, retaining around seven percent more.

It is estimated that employment will increase by as much as 15 percent, as the new, improved locks go into action. By 2025, when the canal is expected to be working at capacity, it should be earning over $600bn annually.

But there are clear challenges ahead. There are plans for a rival canal to be built in Nicaragua with the backing of a Hong Kong telecoms tycoon. The new canal could be open for business in as little as a decade, and though it would be 260km long, much longer than Panama, it will be able to accommodate supertankers much more comfortably. Though nothing has been confirmed yet, it seems the more successful the Panama Canal is, the more competition it is likely to face.

Future

Structural constraints mean the Panama Canal will face increasing competition from routes that accommodate mega-vessels – unless it is willing to continue investing.

Because of its strategic position, the Panama Canal is likely to remain a pivotal route for shipping vessels. But despite expensive expansion of the waterways, there has been some criticism of the Panama Canal Authorities. What was supposed to be a seven-year growth project is late and rife with disputes over costs and who should foot the bill.

There are plans for a rival canal to be built in Nicaragua with the backing of a Hong Kong telecoms tycoon

There has been an ongoing dispute between the Panama Canal Authority and a consortium led by Spanish construction company Sacyr, over the funding of the project. Were it not for mediation by the European Union, the project would have shut down, which would have had catastrophic consequences for the global shipping industry.

As demand for more efficient shipping vessels and faster maritime transportation grows, it is inevitable that it will face greater competition. The Nicaragua canal project might still be in the pipeline, and there has been nothing but speculation about a possible rail link in Colombia, but the Suez Canal has been attracting significant traffic recently.

Chief among concerns about the canal’s future is how it will handle ever-increasing ship sizes. Even with the new third lock, designed for bigger ships, the largest vessels already in use today will not be able to make it through. It has been estimated that by 2030, close to three-quarters of all ships will be mega-vessels, and there is no guarantee they can traverse the canal at all.

Even though the current renovation is a step in the right direction, keeping the canal viable will always be a work in progress. Already, three major shipping companies that import goods into the US are starting to dock in the West Coast, and if this emerges as a trend, it could have catastrophic consequences for port cities in the East Coast, and for the Panama Canal.

But the Panama Canal Authority is not ready to concede – by the company’s own prediction, the canal will double revenue to £6bn by 2025, justifying the $5.2bn price-tag for the expansion. Furthermore, the canal is the backbone of the Panamanian economy and in 2006 the population voted overwhelmingly in favour of expansion; for Panama, this project is too big to fail. For the US, the project is also of vital importance.

“As the energy production throughout the Americas grows, Panama is going to play a critical role in bridging energy supplies in the Atlantic with a growing demand in the Pacific,” explained Vice-President Joe Biden, in a state visit to the construction site in 2013.

There are also a number of environmental concerns that affect the canal, not least of which is the contamination of fresh water supplies. The renovations have addressed this in part, but there are still millions of gallons of dirty water being flushed out to sea in the Gulf of Panama, and the carbon footprint of ships travelling through the canal is astronomical.

But if the Panama Canal Authority is happy to keep investing, and has the foresight to adapt to changes, then the Panama Canal will indubitably remain at the forefront of shipping infrastructure – despite surpassing its hundredth birthday.

A high price for Arizona

by Hudson Powell

The expansion of the Panama Canal has brought about unwelcome competition for logistics companies on the West Coast of the US. If the $5.25bn project is successfully completed, increasing the Canal’s capacity to serve larger vessels, trade will be drawn away from the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach in favour of ports on the East Coast. Changes to Asian trade and shipping routes could have the most impact, as countries such as Japan and China currently distribute goods to the eastern states of the US and the Gulf of Mexico by docking at West Coast ports and continuing the supply chain via rail and road. The widening of the Panama Canal will allow Asia to distribute goods via water routes only. The Arizona Republic reports that 70 percent of Asian trade is at stake.

Arizona is particularly concerned, as a reported eight million commercial journeys are across the state on east-west routes. Furthermore, thousands of Arizonan jobs in the wholesale and retail industries are on the line if the two Californian ports are rejected in favour of the Panemese route. There are multiple warehouses belonging to Amazon, Target and other large retailers that would become redundant if Asian shipping companies made the transition. “We look at these ports in Southern California as our gateway to global markets,” said John Halikowski, Director of the Arizona Department of Transportation.

Of course, one state’s loss is another’s gain, with many East Coast politicians and businessmen rubbing their hands in anticipation of the canal’s enlargement. Ports from New York to Miami have invested heavily on the presumption that Asia will change course, building new tunnels and dredging their harbours to accommodate new business. “There will be a significant amount of additional shipments that will come to the East Coast, rather than go to the West Coast,” Florida’s Governor Rick Scott told radio station NPR last November. “By investing now, we have the opportunity to get companies to expand here, grow here.”

While it is true that large-scale changes to shipping routes takes time, and some organistaions such as the Union Pacific Railroad think the cost implications of water-only routes are too severe, there is strong cause for Western US logistics companies to be concerned.

Timeline

1869

Ferdinand de Lesseps completes work on the Suez Canal and American President Ulysses S Grant sends a commission to investigate the possibility of a similar canal in Panama

1879

The French government approve Lesseps’ plan for a sea-level canal. Construction begins in December

1883-84

An epidemic of yellow fever followed by an outburst of dysentery incapacitate large swathes of the French workforce

1888

Lesseps hires Gustav Eiffel to build locks to stop mudslides that have been hindering excavations

1893

Lesseps is found guilty of fraud and misadministration of the Canal. The French effort is abandoned

1903

Panama declares independence from Colombia. A treaty is signed between the new government and the US, giving the Americans the right to build a canal, for $250,000 annually

1904

John Findely Wallace is appointed chief engineer. Work starts again

1905

Wallace resigns and is replaced by John Stevens, who starts a drive for proper sanitation to avoid more disease outbreaks

1906

Workers begin to clear the site for the Gatún Dam

1907

Lt Colonel George Goethals replaces Stevens as Chief Engineer. Over 800,000 cubic yards are excavated in July

1911

Locks start to be assembled in Gatún

1912

Construction wraps up, but final adjustments must still be made

1913

After a final push in construction and excavation, water flows uninterrupted from the Pacific to the Atlantic

1914

Canal officially opens in August